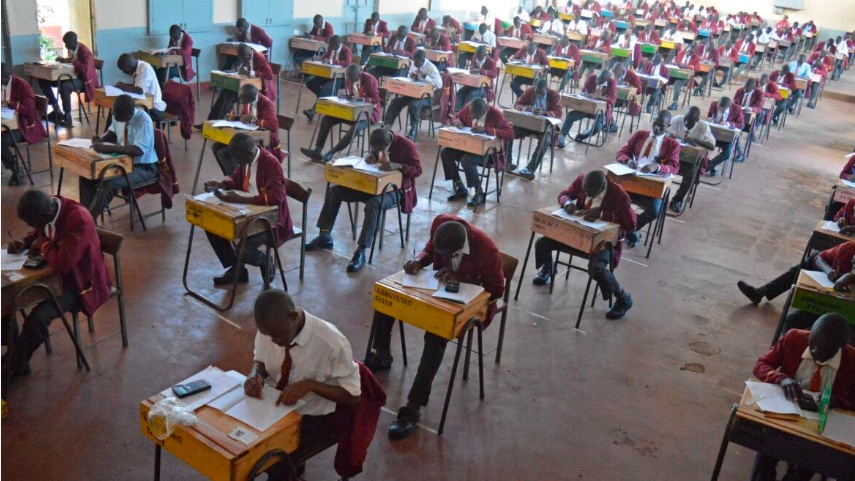

As the 2025 KCSE results approach, Kenya faces a familiar question: Will checking your exam results cost KES 30, or will it just cost you hours of frustration? The answer reveals deeper problems with how we deliver digital public services.

Every January, a familiar ritual plays out in Kenyan households. The Education Cabinet Secretary announces the KCSE results are ready, and within seconds, a digital stampede begins. But unlike previous years, what happens next has become unpredictable.

Will there be an SMS code? Will it cost money? Will the portal work? In 2024, the Ministry scrapped the premium SMS service entirely. For the KJSEA (Grade 9) results months later, it quietly returned at KES 30 per query. Now, as we approach the January 2026 release of 2025 KCSE results, nobody knows which system will be in place.

This inconsistency isn't just inconvenient—it reveals a government that can't decide whether exam results are a public service or a revenue opportunity.

The Tale of Two Approaches

2024 KCSE: The "Free" Experiment

In a move that surprised many, the Ministry of Education eliminated the premium SMS code for the 2024 KCSE results. It was a victory for advocates who argued that accessing exam results—something candidates had already paid registration fees to sit for—shouldn't cost extra.

Then reality hit. The results portal crashed almost immediately. For hours, results.knec.ac.ke was either completely inaccessible or so slow it was effectively useless. Parents refreshed frantically. Students stared at loading screens. Schools struggled to access results for their entire cohorts.

But here's what's interesting: The Ministry didn't bring back the SMS service. Despite the chaos, despite the mounting complaints on social media, they held the line. If you wanted your results, you waited for the portal to stabilize, or you went through your school.

It was painful, but it was free.

KJSEA 2024: The Quiet Reversal

A few months later, when Grade 9 KJSEA results were released, the premium SMS code was back. No press conference. No explanation for why this exam deserved different treatment. Just a quiet return to the old model: KES 30 per query, sent to code 20076.

The message was clear: The Ministry hadn't actually committed to free access. They'd just removed it for one exam, under pressure, and reverted to the profitable model when they thought fewer people were watching.

So What's the Plan for January 2026?

This is where it gets genuinely interesting, because right now, nobody knows. Will KNEC follow the 2024 KCSE model (portal only, no SMS)? Or will they follow the KJSEA precedent and reintroduce the premium service?

The decision matters because it reveals whether the Ministry sees exam results as:

A public service (like accessing your ID information or birth certificate records—things you've paid for through taxes and fees)

A commercial product (like premium content or value-added services)

The Revenue Question

Let's talk about what's actually at stake financially. With approximately 1M candidates sitting the KCSE, and factoring in parents, guardians, schools, and multiple queries due to anxiety or system delays, a KES 30 premium SMS service could generate KES 80-120 million in the first 48 hours.

That's not insignificant money, even for a government agency. But context matters: KNEC's annual budget allocation is approximately KES 8 billion (5.9 billion 2024/2025). Exam registration fees from candidates contribute significantly to operations. The organization is not struggling for resources.

So this isn't really about cost recovery—it's about whether the government should extract additional revenue from an already-captive, already-paying audience at their moment of maximum anxiety.

The Infrastructure Problem Nobody's Solving

Here's the frustrating part: The technical solution to portal crashes isn't mysterious or prohibitively expensive. Every year, predictable events create massive traffic spikes that modern infrastructure handles routinely:

When Safaricom releases new eSIM promotions, millions check at once. The system holds.

When KRA's iTax deadline approaches, hundreds of thousands file simultaneously. It's slow, but it works.

When concert tickets for major artists go on sale, platforms like Ticketsasa handle the surge.

The technology exists. Cloud platforms like AWS, Google Cloud, or even regional providers like Seacom offer "auto-scaling"—infrastructure that automatically expands capacity during traffic spikes and scales back down afterward. You pay only for what you use.

A properly configured system could handle 10 million simultaneous requests without breaking stride. The cost would be a fraction of one percent of KNEC's annual budget.

Why It Doesn't Get Fixed

This is where we need to talk about incentives. If you're a government agency and:

Your portal crashes every year, driving users to premium SMS

The SMS service generates millions in revenue

Nobody faces consequences for the portal failure

Fixing the portal would reduce SMS revenue

...what's your incentive to actually fix the problem?

This isn't necessarily malicious. It might just be organizational inertia, competing budget priorities, or lack of technical expertise in decision-making roles. But the effect is the same: A system that profits from its own failure has no urgent reason to improve.

The International Comparison

Kenya loves to call itself the "Silicon Savannah," and in many ways, we've earned that title. M-Pesa revolutionized mobile money. Nairobi hosts innovative tech startups. Our developer talent competes globally.

Yet when it comes to basic digital government services, we're behind our regional peers:

Uganda: UNEB exam results are accessible free via USSD code and web portal

Tanzania: NECTA results are available at no cost through multiple channels

Rwanda: Exam results are delivered free through the Rwanda Education Board portal

These aren't wealthier countries with better infrastructure. They've simply made a policy decision: exam results are public information that should be freely accessible.

The Class Dimension

There's also an equity issue nobody talks about. For middle-class families, KES 30 seems trivial—barely the cost of a soda. But consider:

A family with three children checking results multiple times: KES 180-300

Rural families buying airtime specifically for this purpose

Students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds for whom KES 30 represents a meaningful expense

The people most burdened by premium charges are precisely those least able to afford them. Meanwhile, affluent families can wait comfortably for the portal to stabilize, or have schools check on their behalf.

This turns exam results into a two-tier system: Fast and reliable for those who can pay, slow and frustrating for those who can't.

The Accountability Gap

Perhaps the most troubling aspect is the complete absence of accountability. When the portal crashes, who's responsible? When wrong results are sent via SMS (as happened in previous years), who compensates affected students? When infrastructure fails year after year, who faces consequences?

In the private sector, consistently failed service delivery has repercussions: Customer loss, regulatory penalties, executive turnover. In government digital services, failure is just... absorbed. Complained about on social media, then forgotten until next year.

There's no public reporting on:

How much revenue the SMS service generates

Where that revenue goes (retained by KNEC? Remitted to Treasury?)

What infrastructure investments have been made to prevent future crashes

What performance standards KNEC is held to for digital service delivery

What Should Happen (But Probably Won't)

The solution isn't complicated:

Invest in proper infrastructure: Migrate to cloud services with auto-scaling. Budget: ~KES 10-20 million for setup and first-year operations—a rounding error in KNEC's budget, and less than what one year of SMS revenue generates.

Make results free by default: Follow regional precedent. If a premium "fast-track" SMS option exists, it should be a convenience for those who want it, not a necessity because the free portal doesn't work.

Implement idempotency protection: Ensure duplicate SMS queries within short timeframes aren't charged multiple times.

Establish accountability metrics: Set public service-level agreements (SLAs). If the portal is down for more than 2 hours on results day, someone should answer for it.

Publish revenue and spending reports: Full transparency on what the SMS service generates and how those funds are used.

The January 2026 Prediction

Based on past behavior, here's the most likely scenario:

KNEC will launch the 2025 KCSE results with a portal-only approach, maintaining the 2024 KCSE precedent. The portal will crash or become unbearably slow within the first hour. Social media will explode with complaints.

Then, one of two things happens:

Scenario A: They ride it out like 2024, and after 6-8 hours, the portal stabilizes as traffic decreases. Students and parents endure the frustration, but at least it's free. The Ministry takes some criticism but can claim they kept results free.

Scenario B: Under mounting pressure and seeing an opportunity, they "respond to public demand" by quickly reintroducing the SMS service as an "emergency alternative." This frames the premium charge as a solution rather than a cash grab. Revenue flows in, and the precedent for paid access is re-established.

My money is on Scenario A, simply because reverting to paid SMS after publicly committing to free access would be politically awkward in an election cycle. But the fact that KJSEA kept the premium service suggests the Ministry hasn't philosophically committed to free access—they've just selectively applied it.

The Real Question

The debate shouldn't be "SMS or portal?" or "KES 30 or free?"

The real question is: Why, in 2026, is Kenya's government still unable to reliably deliver text-based public information to its citizens?

We've built systems that handle billions of shillings in mobile money transactions daily. We've created platforms for tax filing, business registration, and land records. Yet every January, we act surprised when a results portal—essentially a database lookup—collapses under predictable load.

This isn't a technical problem. It's a priorities problem. And until there's genuine accountability for digital service delivery, until there's transparency about costs and revenues, and until we collectively decide that access to public information should be a right rather than a privilege, we'll keep having this same conversation every January.

The Bottom Line

As Kenyan families brace for the 2025 KCSE results release in January 2026, they shouldn't have to wonder whether they'll need to pay, or whether the systems will work. In a nation that calls itself the Silicon Savannah, that pioneered transformative digital services, getting exam results should be the easy part.

The technology to solve this exists. The resources exist. What's missing is the political will to prioritize public service over revenue extraction, and the accountability mechanisms to ensure that when systems fail year after year, someone is responsible for fixing them.

Until then, every January will remain a gamble: Will it be free but broken? Paid but reliable? Both expensive and frustrating?

Kenyan families deserve better than having to guess.

Comments